Updated 8-22-24

We often refer to mobility as the secret weapon of the Core-Tex®. And if you have ever had the opportunity to go through some of the motions and principles described below, you know exactly what we’re talking about.

Whether you are looking for improved performance, rehabbing an injury or avoiding that hip replacement, these moves are for you.

A recent research article on Core-Tex in the International Journal of Research in Exercise Physiology looked at flexibility as one of the four components of fitness utilizing Core-Tex. Improvements were clearly seen post Core-Tex intervention.

The science is there behind the amazing response you get from using the Core-Tex and reactive training for your mobility work. The concept of using subtle, oscillating motions in combination with Core-Tex achieves unique neurophysiological and vector variable, mechanical benefits.

How Oscillating Motion Can Help Your Clients Move Better

Strategic, oscillating movements grounded in evidence-based principles can elicit the neurophysiological pathways and down regulation influenced via manual therapies. These movements can also be used to prepare the body for more global myofascial mobilization movements.

Fascia adapts its fiber arrangement, length and density according to local demands (Findley, 2009). This follows Davis’ Law of soft tissue modeling. Along with this, both macro and micro trauma will have local effects on arrangement, length, and density with global influences on the body. Habitual postures, repetitive movement patterns and a musculoskeletal health history give us insight into the myofascial restrictions that influence the client’s/patient’s movement patterns.

Critical Execution Points

Myofascial restrictions will limit motion at the joints. Stretching or mobilizing techniques that approach a joint’s barrier and stress the joint capsule (intimately tied to the intervening fascia) will discharge joint receptors that up-regulate increased muscle tonus around the joint. In addition, the threshold for discharge is likely to be lower in joints that have previously been damaged and not thoroughly rehabilitated or that have experienced degenerative changes. For example, an unstable ankle joint from a previous ankle sprain may respond to rapid, end range or close to end range loading with increased co-contraction of the peroneals, anterior tibialis, toe extensors and gastroc/soleus complex. Therefore, the movements suggested here work in a range below any barriers presented by the joints or myofascia.

Two key variables associated with the oscillatory motion are rhythm and amplitude.

- Rhythm relates to the tempo and timing of the movement. The movement should be continuous with no pause or delay at either end of the movement. A gentle, controlled momentum utilizing the stored elastic energy of the myofascial line(s) being addressed is used as part of the motion to produce a sense of “rocking.” Rhythmical rocking motions will elicit and calming response to the sympathetic nervous system. The inherent motion created by the Core-Tex facilitates this motion perfectly.

- Amplitude refers to the size of the oscillation created by both the range of motion in the direction of the barrier (tissue tension) as well as the return range of motion in which the tissue tension is disengaged. These movements should not approach the associated joint barrier and maximal tissue tension. Instead, the motion should have small amplitude in both the direction of tissue tension and in the direction where tension is removed. The safety bumper which is part of the Core-Tex design does this for you.

Advantages of Core-Tex Based Myofascial Release

Vector Variability

Most flexibility applications will address the tissue along a specific line of stress. No other lines are influenced until the body is moved or a therapist applies a different angle. This can be time consuming, inefficient and ineffective as hidden lines of resistance can be overlooked.

In comparison, utilizing Core-Tex the individual can immediately access and explore multiple lines of stress just through subtle changes in the movement of Core-Tex.

Huijing (2007) has shown myofascial force transmission between and within muscles, demonstrating connections between both synergistic and antagonist muscles. Within a muscle fiber, up to half of the total force generated by the muscle is transmitted to surrounding connective tissues rather than directly to the origin and insertion of the muscle fibers. Thus, the assumed line of resistance is only half the equation.

When utilizing the multiple vectors with which the Core-Tex can move, we are able to access myofascial limitations specifically along the vectors (paths of lesser tissue compliance) that they are most prominent. The user is able to move the platform and explore where their unique needs are.

Physiological Pumping

When a client actively performs these movements in a gravitational field, the addition of heat and fluid exchange within the tissue created by the muscles associated with the movement (Ingber, 2003). Mechanically, more overall connective tissue can be influenced via movement permitted through the reactive variability of the Core-Tex.

The overall objective of the oscillatory movements is to reduce myofascial tone so that the range of motion can gradually be improved through the targeted myofascial lines by increasing the amplitude of the movements. As tonus is decreased, the oscillations create a pumping action of the tissue. As range of motion is increased, fascial lines in parallel as well as in series are positively affected.

Returning to the ankle joint as the example, limited dorsiflexion is a common movement challenge for many clients. This can be due to myofascial restrictions from the plantar fascia to the hamstrings and/or over activity of the surrounding musculature due to instability-as in the case of chronic ankle sprains.

Conclusion

Strategic movement with reactive training and reactive variability should be an adjunct or complimentary strategy to self-myofascial release (SMR) or other tool assisted devices or manual treatment from a therapist.

In fact, the combination of SMR and dynamic stretching has been shown to be superior then either one on their own (Richman, et. al 2019).

If we can agree that the body is in fact a rhythmic structure, then with oscillating movements you are creating rhythm where rhythm is not present due to myofascial restriction. By following a philosophy of “ask – don’t tell the body,” you can work with the body versus against it to actively improve function of the myofascial system.

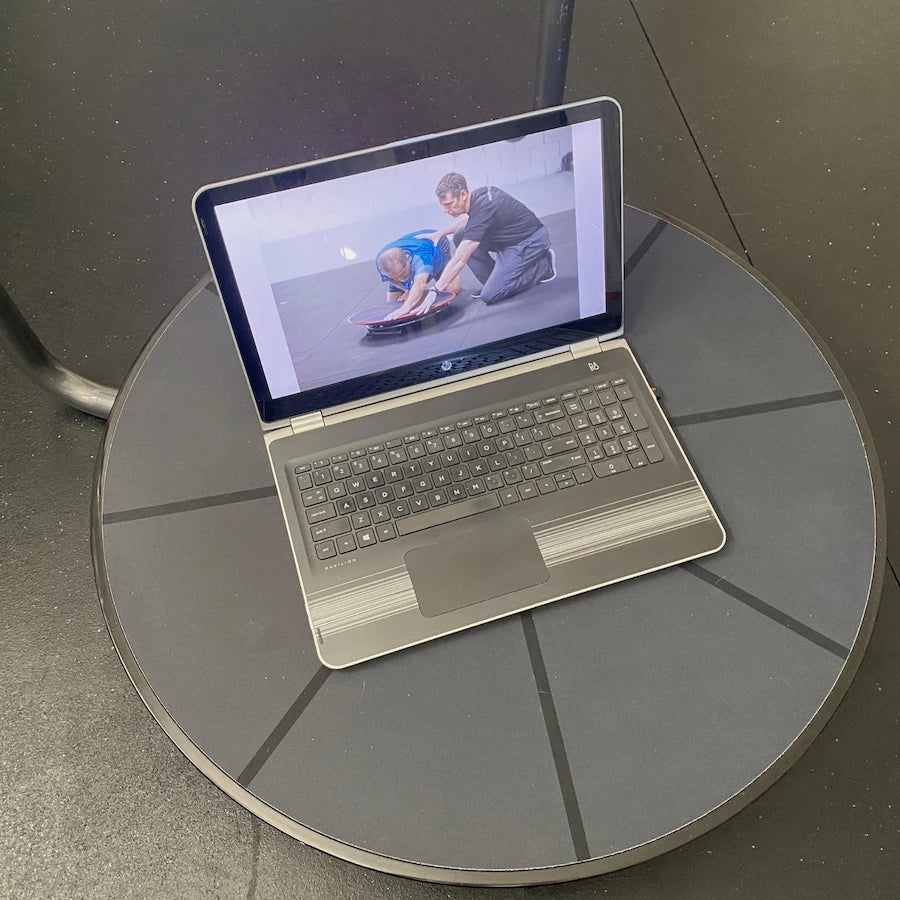

Oscillating Myofascial Release in Action

The video above demonstrates how you can improve one rotational mobility with a traditional front to back exercise.

References

Huijing, P.A. (2007). Epimuscular myofascial force transmission between antagonistic and synergistic muscles can explain movement limitation in spastic paresis. Electromyography and Kinesiology, 17(6): 708–724.

Ingber, D.E. (2003). Tensegrity II. How structural networks influence cellular information processing networks. Journal of Cell Science, 116: 1397-1408.

Richman ED, Tyo BM, Nicks CR. (2019). Combined Effects of Self-Myofascial Release and Dynamic Stretching on Range of Motion, Jump, Sprint, and Agility Performance. J Strength Cond Res. 33(7):1795-1803.

Leave a comment (all fields required)